Github Programming Language Classification

03 Dec 2016 | the Github TeamGithub doesn’t only make version control software; it’s tasked with the unique challenge of analyzing programming languages. With over 10 million repositories, Github has an incredible corpus of files written by over 3 million users… that’s a lot of files. Our team had the unique opportunity of identifying which programming language each file was written in. Our dataset has 50,000+ files with over 600 languages, a nontrivial multi-class problem. We’ve improved on Github’s existing classifier, Linguist, and, in the process, learned about what makes each programming language unique from one another.

Top: Hohsiang Wu, Brandon Lin, Dan Ricciardelli

Bottom: Jin Park, Wesley Hsieh, Olivia Koshy, Jonathan Lee, Rohan Taori

Not included: Jonathan Lee, Michael Zhao, Ted Xiao, Gautham Kesineni

Improvement #1: Dataset

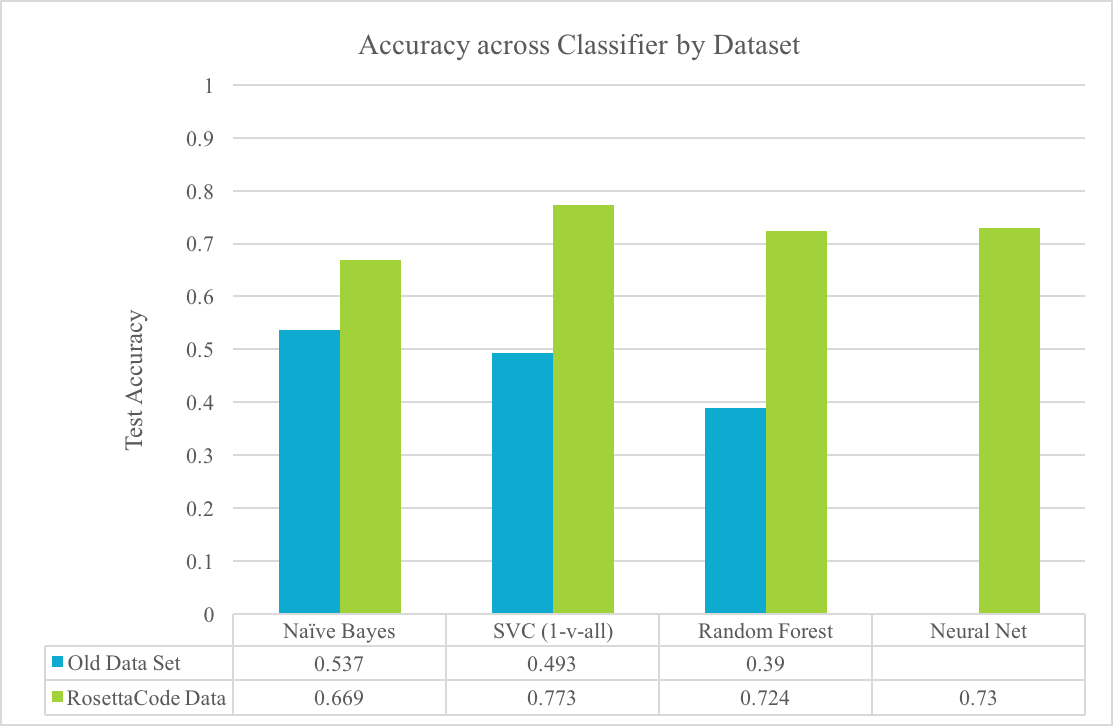

Github’s Linguist has less than 5,000 files in its training data. As a result, their Naive Bayes classifier did not classify real-world files well. Not only that, but their classifier also requires that this dataset be curated and maintained as languages evolve and are added because some of the idiosyncrasies of different programming languages are hardcoded in. We tackled this by scraping Rosetta Code, a site with thousands of files categorized by task and, more importantly, programming language. Shifting from the Linguist dataset to Rosetta Code increased our test accuracy by 13.2%. Training accuracy went down as expected, because the Linguist classifier overfit to the smaller dataset. This is not concerning because test accuracy is really the metric that counts, and our higher test accuracy indicates that the larger dataset lets us generalize better to new, previously unseen files.

| Train | Test | |

| Old Linguist Data Set | 94.7% | 53.7% |

| New Rosetta Code Dataset | 85.6% | 66.9% |

Improvement #2: Feature Engineering

Github’s current classifier relies on bag-of-words methods to classify files, which means it can run into trouble differentiating programming languages with similar common statements. For example, C and C++ cannot be easily differentiated just by looking at which words are used. For ambiguous cases, Github’s Linguist hardcodes features that are unique to a particular language to distinguish between similar ones. Unfortunately, these hand-engineered features take significant time to construct and may change as languages evolve.

Because of this, our team has taken the prototypical bag-of-words approach and augmented it with linear and nonlinear features learned from data rather than constructed to match the data. For example, our team is currently modeling new features based off of features learned by RNN’s. This data-centric approaches scales well, grows easily to fit larger datasets, and requires much less human supervision on Github’s end.

These new features, both drawn from the raw data and learned by models, have allowed us to increase our classification accuracy from ~60% to 79-81%.

Improvement #3: Model Types

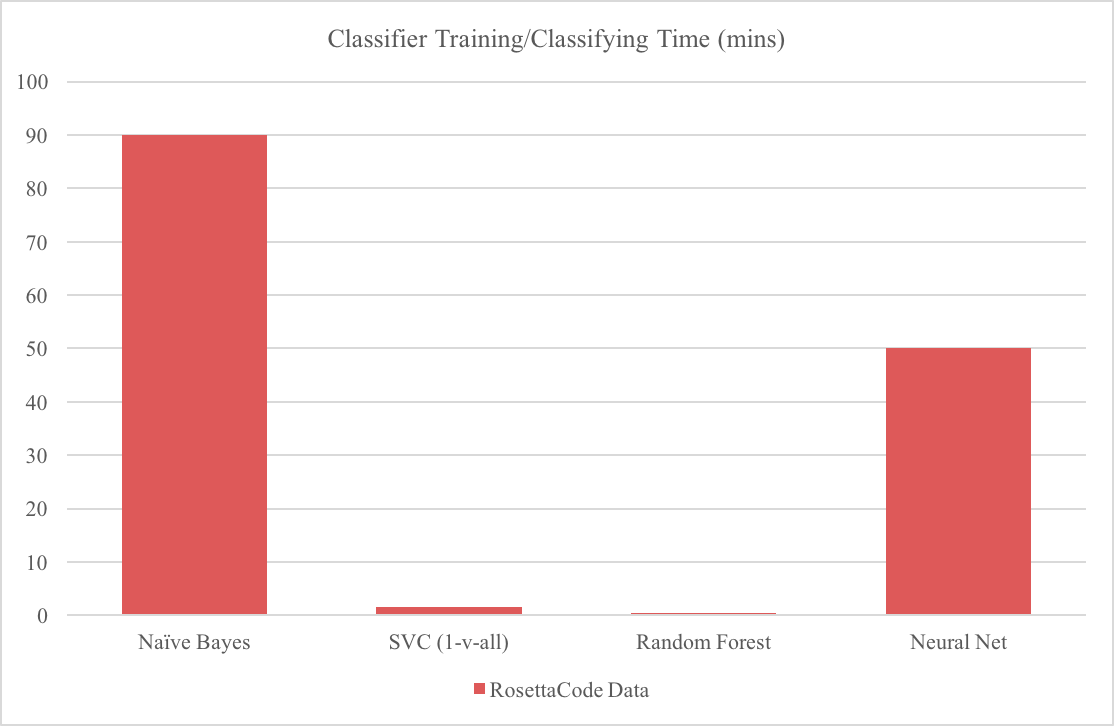

Github’s previous Naive Bayes Classifier may be, well, naive, but that doesn’t mean it does a poor job. Bayesian classifiers work rather well with small datasets and integrate well with heuristic knowledge about the problem. However, Naive Bayes can be slow to train and classify files, may not generalize well, and requires human supervision to maintain well-behaved heuristics.

Our first new model is a multi-class Linear SVC. Linear SVCs are the classification variant of the popular SVM, which aims to divide the data points by class such that the minimum distance between the decision boundary and either class is maximized. This results in a classifier that is both robust, as it is highly linear, and complex, as many input features are non-linear.

We also used decision trees, chosen to mimic Linguist’s heuristic decision making process, and neural networks, chosen to deal well with reducing the sparse high-dimensional problem into something more tractable.

Improvement #4: Error Metrics

It’s easy to feel comfortable about a model’s performance when it has been constructed to work well with the dataset. Even with a larger dataset, more carefully constructed error metrics allow us to guard against overconfident accuracy reports and to examine where our models are failing. Our team tested our models with stratified cross-validation (which is a way testing how well a model works) to ensure truthful accuracy measures by language and is working on an error metric pipeline so that Github can easily examine where their models are falling short and what can be improved.

Conclusion

Fourteen weeks of part-time work is not nearly enough to explore this problem, and ML@B’s Github team only touched the tip of the iceberg by finding a larger dataset, extracting machine-learned features, comparing different model types, and exploring various error metrics. There were many iterative improvements that are not mentioned in this post, but can be found here. All experiments that we conducted to improve our classifier can be replicated in our code. If you are interested in contributing, email machinelearning@berkeley.edu.